Updating 1984 with The Circle/ Changes in Surveillance Conceptions

Part 1: Surveillance & Panopticism

Introduction

Anxieties about surveillance lurks in the background of our everyday lives. The idea of being watched by opaque actors for unclear reasons makes many of us act out in vaguely informed ways, such as blocking webcams and turning off location-tracking on our devices. This unarticulated, intuitive, and pervasive sensibility has been called paranoia.

Paranoia is a persistent theme in twentieth-century fictions, famously expressed by writers such as Franz Kafka, whose 1925 novel, The Trial, is still considered to be the standard for paranoia fiction.[i] Here a defining feature of paranoia fiction is the staging of the main, identifying character as the target of unjust or unclear prosecutions by an omnipresent and omniscient authority. This prosecution-complex could either be imagined or proven real, sometimes a surreal mixture of both. 24 years after The Trial, George Orwell published Nineteen Eighty-Four. This work, amongst other things, still represents the dystopian subgenre of science fiction that has mass surveillance as its primary setting-element and prosecution its core theme. I’ll label this subgenre as surveillance paranoia fiction.

Today in 2020, seventy years after Nineteen Eighty-Four, our technological environment has seen some changes. Here, many[ii]/[iii] have pointed to Dave Egger’s 2013 novel, The Circle,as an update of Orwell’s surveillance paranoia fiction.Despite issues in writing and world-building, The Circle is a straight-forward expression of a kind of paranoia that many may have in the present moment. In this two-part essay, I’d address the surveillance technologies in Nineteen Eighty-Four, then those in The Circle, and finally present some theories on how we could understand what surveillance means. As usual, without discussing-thus-spoiling the story elements, this essay directs attention to the novums, that is, the speculative technologies or practices.

Telescreen and the Surveillance Camera

The novums of Nineteen Eighty-Four are now quite well known and have become a part of our common vocabulary. Such as the “Telescreen,” “Newspeak,” “Thought Crime,” “2+2=5,” and so on. The surveillance apparatus of the setting involves both soft and hard infrastructures. Simply put, soft infrastructures are the entrenched concepts and practices; such as the Thought-Police, an organization tasked to identify and arrest people on the basis of having beliefs deviating from “Ingsoc” (the state-ideology in the setting). Hard infrastructures, on the other hand, are the material technologies necessary for certain soft infrastructures to operate. Here, I’d isolate one such technology to represent the surveillance apparatus of the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four—the telescreen.

The telescreen is a media that serves at once as a surveillance camera with a microphone, a television, and a one-way broadcast speaker. The telescreens are installed in public spaces and in the homes of the party members, including our protagonist, Winston. It displays a constant stream of propaganda, and cannot be turned off. As a surveillance tool, the telescreen is monitored by the Thought-Police. Even though it doesn’t have night vision capacities, its equipped with a microphone sensitive enough to pick up the human heartbeat, therefore one is not outside of surveillance even in the dark. No one could know when a telescreen is being watched by the Thought Police at any given time, but anyone within its view is preconsciously aware that they could be watched at all times.

In real life, what’s commonly known as the surveillance camera, or closed-circuit television (CCTV), is the historical precursor of Orwell’s fictional telescreen. Some had argued that the first was designed by the Russian polymath, Leon Theremin,[iv] in 1927. Its development was limited, and was installed only in the Kremlin courtyard. The first commercial CCTV system, Vericon, appeared in the US in 1949, it was then called the “television camera.” Twenty years later, Olean, a city in New York was the first recorded city in the US to have installed camera-systems in public spaces for fighting crime.[v] Today, it seems banal to say that the camera-system is a pervasive fixture in public and private spaces.

The Panopticon

But if we want to identify the origins of the more abstract design logic of visual surveillance, we could trace to the English philosopher, Jeremy Bentham’s concept of the Panopticon, which was visualized in 1791,[vi] nearly two centuries before first publicly installed CCTV system. As an architectural model, the Panopticon was designed in a way in which the prison subjects would be aware of an invisible inspector and their own constant potential of being watched, which in effect move them to self-regulate their own behaviors to avoid punishment.

Here, the philosopher Michel Foucault famously argued that this ‘panoptic logic’ was a common model of governance for the social institutions that were steadily emerging in Europe since the 18th Century.[vii] Various forms of such institutions—such as factories, prisons, schools, and asylums—are managed through an underlying philosophy of panopticism. Which is a combination of being seen by the unseen authority, punishment avoidance, and self-discipline—a set-up aimed to produce docile bodies, that is, people who have been trained to intuitively act and think in specific ways within a given institution.

In the case of schools for example, this means keeping silence in the classroom, talk only when you’re given permission to, admitting the teachers as the authority for the measure of your worth, and so on. These habits are trained or internalized through spending years in such environments, under the surveilling gaze of the teachers, the superintendents, and sometimes, the police. To the effect that once people graduate from such settings, they would still act and think in disciplined ways without the presence of surveillance. This is, in Foucault term, the main feature of the Disciplinary Society—a panopticon internalized, in the societal-scale unconscious.

Conclusion

Now, where does The Circle come in? I’ll get into that in the second part of this two-parter. For now, I’ll mention that the real-life security-camera systems and 1984’s telescreens are what you would call: stationary sensing systems. That is, their sensing capacities are limited by their situation in space: at a street corner, by the traffic intersections, in the workplace, in one’s home and so on. And like the supervisors of the panopticon: the teachers, the cops, and the managers are all spatially located. The Circle, on the other hand, represents an updated picture that reflects today’s less spatially bounded, more liquid surveillance paradigm, and its related, more ambient form of surveillance paranoia. Namely in our age of ubiquitous computing—as composed of smart devices and mass market digital platforms.

Part 2: Ubiquitous Computing & Control-Society

Introduction

In the second of this two-parter, I’ll present how Dave Egger’s The Circle has been seen as an update of Nineteen-Eighty-Four, one that serve as a reflection of our current era of ubiquitous computing and the more ambient surveillance paranoia surrounding it. These two works would be framed here as two models of governance, one being the form of space-bounded discipline, and the other a form of trans-spatial control, which I’ll get to in a moment. Further, I’d complicate what seemed to be an implied theme until now: that discipline is repressive, oppressive, or anti-human. Because, we should have some disciplines, right? Imagine someone undisciplined to the traffic rules. I’ll conclude by indicating how ‘surveillance’ could be understood, and perhaps how the concept should be subordinate to higher perspectives.

The Blueprint of The Circle

Eggers’s (transrealist[viii]) novel is set in the near future, revolving around one megacorporation, ‘The Circle,’ which could be seen as an amalgamation of the real-life GAFA corporations (that is, Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon) and in the Sinosphere, the BAT corporations (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent). This organization is a monopoly that covers all data-related services and the design of consumer devices, eventually operating at the global-scale. It owns and manages both the hard and soft infrastructures for those operations, which, although Eggers did not specify, may include the entire infrastructural ecology from satellite systems, data centers, fiber-optic networks, urban-scale sensors, and personal devices, to the software platforms, which may involve the capture, storage, sorting, and using of user-data. In short, the Circle represents a total, coherent, thus paranoid, ideal-image[ix] of present-day ‘big tech.’

I’d consider this corporation as one novum. For the applications and devices designed by the Circle all cohere into one omnipotent and omniscient model. In other words, what is interesting is the model itself, which is a composition of designs, practices, and infrastructures. The Circle is essentially offering a universal all-purpose social media platform, with online wallets and banking functions tagged on—this platform was named TruYou.[x] We could imagine the TruYou platform as an amalgamation of present-day Internet forums, Facebook, Twitter, Apple Pay, online banking, and so on. Which means, effectively, everything about a person—data of their histories, preferences, relations, biometrics, and so on—are compiled in one’s unique profile on the platform. And each profile is representative of one and only one person. Such is the basic framework by which other devices and applications are mere extensions: such as the concealable SeeChange sensors, and of course, the smartphones. In short, the Circle constructs a planetary-scale sensing and computing system that envelopes every aspect of life.

This platform’s key feature is that a profile is designed to be transparent and public, meaning everyone’s history and activities are constantly visible for both the Circle and by other users. In the book, this transparency successfully eliminated all possibilities of identity theft, transactional fraud, and online trolling. These effects quickly brought the platform to universal adoption, leading the company’s eventual global penetration. The Circle’s core tenet is total transparency, regardless of one’s social and public status. For example, the SeeChange camera was partly promoted in terms of its sousveillance potential, that is, it could facilitate civilian-level monitoring of the conducts of the police, military, and eventually politicians. Making their every moment visible, therefore accountable.

Control-Society

So, how could we understand the Circle as an expression of the present? And should we? Remember, in Foucault’s concept of the disciplinary-society, the human subjects are habituated and shaped through several forms of disciplining institutions, such as the workplace, the school, and the prison.[xi] The people enforcing the discipline (such as workplace managers and school teachers), and their corresponding systems of conducts and regulations, are therefore situated within specific spatial confines.

Since the middle of the Twentieth Century however, the gradual expansion of information technologies to every aspect of life began to change this spatially limited arrangement of discipline. Realized by this ubiquitous computing,[xii] the operations of discipline became despatialized or delinked from the material confines of buildings, such as the school, or the office buildings. This new model was named by the philosopher Gilles Deleuze in 1990 as control-society.[xiii]/[xiv] The core technology of which could be summed up as a sensorial and actionable database.

This database performs what disciplining institutions such as schools were always already doing: which is the sorting of the human subjects according to a set of classifications and the treatment of each group by different actions. In the school context for example, this may mean things like the A grade, the B grade, the failing grade; being absent or present in class; and so on. You experience control-society through being in or out of eligibility or access. Such as: if your grades are good enough to be eligible for certain university. Or which tier of healthcare could access, based on your national- or company-standings.

Or from an architectural angle, the logic of control liquifies the solid disciplinary architectures into networks of checkpoints and enforcers. In the same paper, Deleuze cited his partner-in-crime, Felix Guattari’s fictional city. A city composed of sensor-networks positioned at strategic checkpoints between zones, serving to identify the access privileges of people’s electronic cards, letting some in and keeping others out.

Building on Deleuze’s control-society concept, Haggerty and Ericson in 2000 observed[xv] the emergence of a form of identity composed entirely by data such as school grades, criminal records, credit ratings, shopping records, likes, clicks, and so on. They named it data-double: which is you as the ghostlike composition of your records and classifications in databases—databases that sort and give people differential treatments accordingly. The security checkpoints at airports would be an example of this sorting. Or less obviously, the banks function as a checkpoint for sorting peoples with higher credit ratings to be given mortgage.

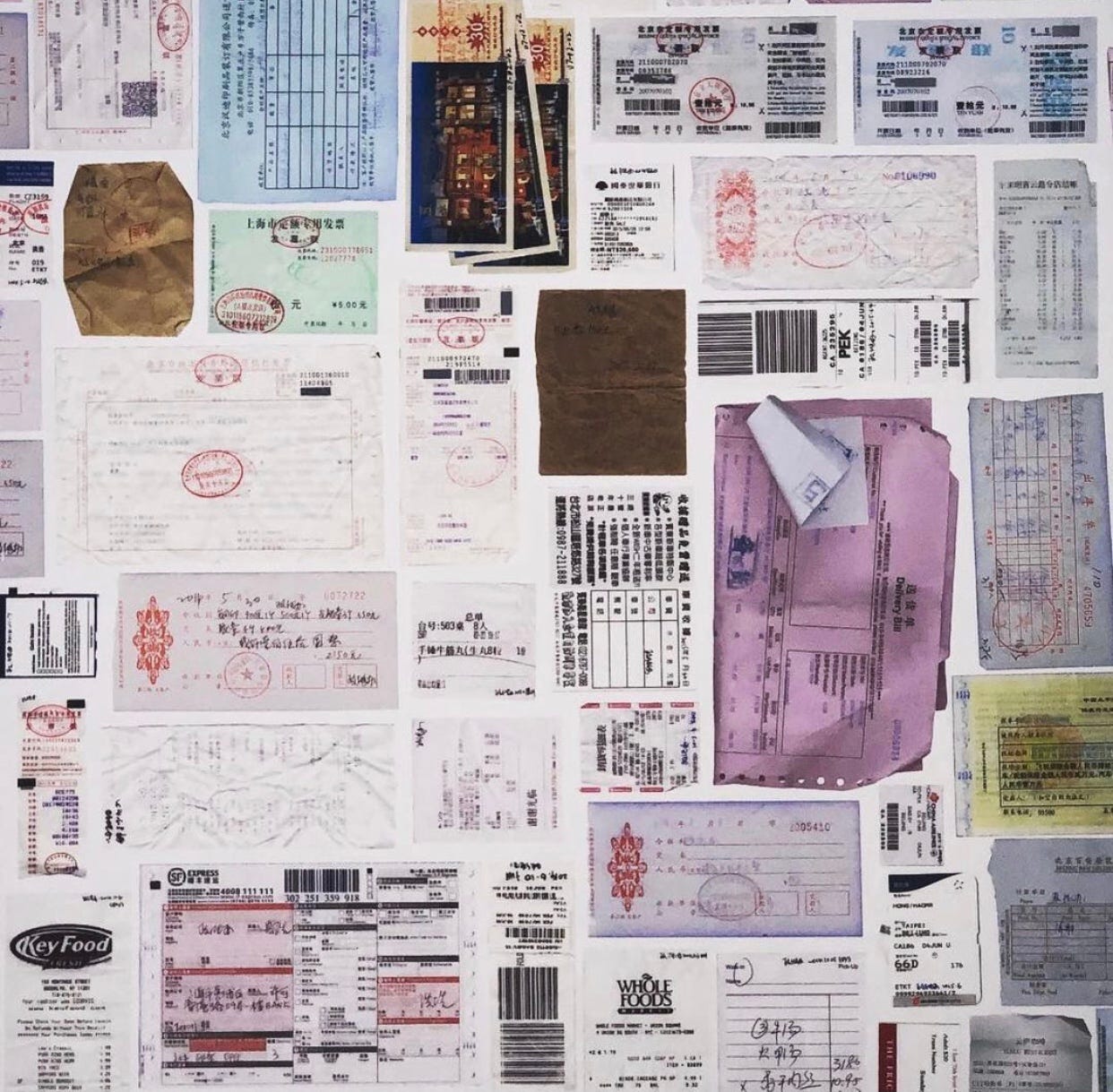

The Circle’s TruYou platform expresses the anxiety of data-double becoming a reality: that is when databases are unified and integrated. Although it could theoretically happen, it isn’t yet a reality. How would you find out? Just think of the Kafkaesque amount of documents you have to compile by yourself when you’re applying for job, school, or immigration. It is still up to individuals to compile their own data-doubles. The exceptions being, of course, when you’re under some criminal, civil or tax investigations, in which case someone else would compile your dossier for you.

Conclusion

To conclude, I should note that the logic of control doesn’t necessarily need ubiquitous computing to operate. An analogue version of a control infrastructure was darkly exemplified in Apartheid South Africa, where cities were partitioned and access points were guarded by patrol officers sorting population flows based on people’s skins and passbooks.[xvi] Some suggested a deep historical relation between identity documentations and surveillance.[xvii] Others would go back further,[xviii] arguing that empire- and state-building inherently demands the construction of legible, and thus classifiable and surveyable identities, for purposes of war, property rights, taxation, law enforcements, and so on. Or for social organization in general, such as enforcing traffic rules.

If I have a thesis here, it’d be that: surveillance should not be perceived as an independent phenomenon—a view which would only generate endless paranoia. But it should be seen as subordinate to the question of classification and sensing, which is in turn subordinate to the question of organization. Institutional classification schemes are the key sites of political struggles in control societies, not surveillance. When fixated on surveillance as such, people would only be paranoid about being confirmed as deviant, instead of attending to the more important question of: what are classified as deviant, and why?

—————————

[i] Spurr, David. 2011. “Paranoid Modernism in Joyce and Kafka.” Journal of modern literature 34(2):178-191

[ii] Lyon, David. 2018. The Culture of Surveillance: Watching as a Way of Life. Cambridge: Polity Press.

[iii] Jarvis, Brian. 2019. “Surveillance and Spectacle Inside The Circle.” Pp. 275-294. in Surveillance, Architecture, and Control: Discourses on Spatial Culture, edited by S. Flynn and A. Mackay. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

[iv] Glinsky, Albert. 2000. Theremin : ether music and espionage. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

[v] Robb, Gary C. 1980. “Police Use of CCTV Surveillance: Constitutional Implications and Proposed Regulations.” University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform 13(3):571-602.

[vi] Gold, Joel and Ian Gold. 2015. Suspicious Minds: How Culture ShapesMadness. New York: Free Press.

[vii] Foucault, Michel. [1975] 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York, US: Vintage Books.

[viii] Rucker, Rudy. 1983. A Transrealist Manifesto. http://www.rudyrucker.com/pdf/transrealistmanifesto.pdf

[ix] Or “ideal-type,” in the Weberian sense.

[x] Eggers 2013:21

[xi] Foucault, Michel. [1975] 1995. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York, US: Vintage Books.

[xii] Weiser, Mark. 1991. “The computer for the 21st Century.” Scientific American 265(3):94-104. https://www.ics.uci.edu/~corps/phaseii/Weiser-Computer21stCentury-SciAm.pdf

[xiii] Deleuze, Gilles. [1990] 1992. “Postscript on the Societies of Control.” October, 59:3-7. https://www.blogs.hss.ed.ac.uk/crag/files/2015/09/deleuze_control.pdf

[xiv] Deleuze’s diction is obviously the more famous one. But several other articulations have emerged around the 1990 mark. Such as “dossier society” (Kenneth Laudon 1988) and “dataveillance” (Roger Clarke 1988).

[xv] Haggerty, Kevin D. and Richard V. Ericson. 2000. “The Surveillant Assemblage.” British Journal of Sociology 50(4): 605-22.

[xvi] Bowker, Geoffrey C. and Susan Leigh Star. 2000. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. Pp.195-225.

[xvii] Torpey, John. 1999. The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State. Cambridge England: New York : Cambridge University Press.

[xviii] Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing like a State: how certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.